Sticking with my theme of recent weeks, today I’ve got the usual mixed bag of macro news.

On balance I’d say we are just about in the positive territory from a macro perspective but there are still plenty of storm clouds on the horizon.

So, in this spirit of even-handedness let’s start with the all-important subject of corporate profits. We are nearly half way through Q2 European earnings season and according to analysts at HSBC they look “set to deliver another underwhelming result. Just 53% of companies so far have beaten analyst expectations for EPS, down from 56% in Q1. If maintained, this will be the lowest proportion of beats since Q4 2015. This leaves FY 8.5% EPS growth expectations vulnerable. We forecast 5%. Digging beneath the surface highlights domestic names as the main source of weakness – just 49% exceeded estimates vs 56% for more global names. We believe this trend will continue. European activity continues to disappoint, and HSBC sees just 1.9% GDP growth in 2018. Cost pressures are also rising.”

Sector-wise, Consumer Staples have led the way with 89% beats, and HSBC has raised Food & Beverages to overweight, from neutral. On the macro level, the world’s local bank now forecasts that the euro will “continue to weaken, reaching 1.13 by year-end, and this will provide a further boost to exporters. We are underweight Europe ex-UK, neutral UK and overweight Switzerland.”

Back in the UK though there’s some good news on UK dividends – Link Asset Services says that “UK dividends surged 7.1% to a record £30.7bn on an underlying basis in Q2 of 2018. Meanwhile, headline dividends dropped 2.1% year-on-year to £32.6bn owing to sharply lower special dividends than a year ago”. Other key findings include:

- Underlying dividends (excluding specials) surged 7.1% to record of £30.7bn

- Headline dividends dropped 2.1% year-on-year to £32.6bn owing to sharply lower special dividends than a year ago

- Dramatically stronger mining dividends and lower-than-expected exchange-rate penalty explained the strong performance

- Underlying growth forecast raised to 6.9%, bringing a total £94.1bn for the full year

- Headline growth forecast raised to 3.2% bringing the total to £97.8bn for 2018, a new record

So, underwhelming European corporate earnings and abundant UK dividends – not a completely dire picture. But all this corporate data just glosses over the fact that we are midway through a massive expansion in corporate/state balance sheets and debt levels.

Or are we?

Invesco reckons there might be some good news on that global debt mountain. They’ve crunched recent BIS numbers and they reckon that the global debt burden declined in 2017. “Having risen from 172.1% in 2001, the global nonfinancial sector debt-to-GDP ratio declined from 219.5% in 2016 to 218.3% in 2017 – the first such fall since 2010”. Invesco notes in particular that there have been big declines in the Netherlands, Belgium and Spain (all with declines in the debt/GDP ratio greater than 10 percentage points). The bad news is that the US managed a slight decline, largely down to the corporate and public sectors, while China’s debt barely changed during 2017. The biggest rise came in Brazil (a gain of 2.6 percentage points, moving it up the global rankings from seventeenth to sixteenth).

Those numbers from Europe suggest that some countries might have learnt their lesson after the global financial crisis. And what’s generally true is that interest servicing costs have declined dramatically for what’s left of the mountain of debt.

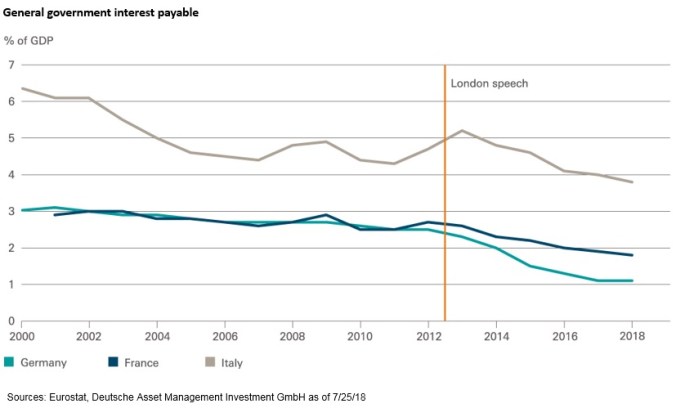

Deutsche Bank reminds is that it is now exactly six years ago that European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi made the famous pledge in London that the ECB would do “whatever it takes” to maintain the unity of the Eurozone. This speech marked an important turning point in the crisis.

Deutsche observes that since then risk premiums have declined and financing conditions have eased again. This is particularly true for public-sector debt. The chart above demonstrates this easing – Italy now spends about a third less on servicing public debt (compared to GDP) than in 2000. According to Deutsche, this “ is all the more remarkable given that Italian public debt has increased from 105% to 132% of GDP over the same period. The German finance minister and his French counterpart have had to allocate less money to servicing interest payments in their budgets, too.”

The downside is that “the boundaries between economic, fiscal and monetary policy have become blurred to an extent we could not even have imagined 10 years ago. This further complicates fiscal and monetary policy in the already complicated post-crisis period. At some point in the future, that could well give us a headache. More progress, notably on the integration of European capital markets, would be highly welcome.”

In other words, public services will be crushed if those interest rates were to ever increase markedly again. All that Europe needs now is more growth. But as HSBC indicates, corporate profits are still anaemic. A work in progress.

Leave a Reply